NEW INTERPRETATIONS

OF FRANCO-CANTABRIAN

PALEOLITHIC

PAINTINGS

A brief revision of Franco-Cantabrian paintings of the paleolithic period and new interpretations of their meaning: to provide a virtual dwelling place for spirits and to aid reproduction.

A brief revision of Franco-Cantabrian paintings of the paleolithic period and new interpretations of their meaning: to provide a virtual dwelling place for spirits and to aid reproduction.

Una breve revisión de las pinturas

franco-cantábricas de la era paleolítica y nuevas interpretaciones sobre

su significado : para proporcionar una morada virtual para el espíritu del animal y

favorecer la reproducción.

Author : Rafael Menéndez García

INTRODUCTION

When we talk about art in caves, the first thing we usually think of are the images of bison painted on the walls and celings of caves, particularly those in Altamira in Northern Spain, or bulls and horses found in Lascaux, in the south of France. Indeed, the region stretching between and around these two points is where the greatest abundance of this kind of art can be found; at least 200 caves featuring paintings or engravings on the walls and, less commonly, sculptures. There is little variation in terms of subject matter, style and conception between cave paintings found in this area and they are so homogenous that the Franco-Cantabrian style has been established.

What is generally accepted to be the earliest form of painting in caves which remains to this day are handprints, probably dating from the end of the Aurignacian period or the beginning of the Solutrean. This latter period seems to have seen the appearance of paintings deep inside the cave and more importantly, large carvings in bas-relief which are principally found in France. It was in the next period, the Magdalenian, that cave painting truly thrived, reaching its zenith in terms of quality in the early part of this timespan. In fact, the Magdalenian makes up some 80% of all cave paintings discovered.

Apparently, there were some parts of the caves more in demand by the painters, where we can find a mass of images painted using different techniques, with a different orientation and on a different scale. In these scenes, or panels, the animals overlap each other constantly in an apparent attempt to make as much use as possible of the space provided and strokes or basic shapes made by a previous painter may be taken advantage of by another to create a new animal. Sometimes, it would seem that the original painting has been rubbed out to make room for the new, as we can still make out the remains of paint on the wall. On the other hand, we can also find single paintings in a remote part of the cave, totally hidden from view. A flat surface was not always used. Quite the contrary, in fact, as often protuberances or rougher areas of the surface seem to have suggested the shape of the animal to the painter and in these cases this uneven surface, a crack or hole in the rock and even the shadow projected was usually incorporated into the image.

PREVIOUS INTERPRETATIONS

Bearing all this in mind, we should ask ourselves if the paintings were, in fact, meant to be viewed by anyone at all. Was it the intention of the painters to create what we call art? Were they seeking the admiration of their fellow man, or indeed of generations to come? Were they trying to leave their mark for posterity? We think it is time to take a fresh look at cave paintings but first we will summarise the theories that have aready been proposed as follows:

1. Art for art's sake

The idea of art for art's sake was the first, proposed as long ago as 1864 by Lartet and Christy, who claimed that as a result of abundant hunting and hence economic prosperity, Man was left with so much free time that he entertained himself decorating tools, weapons and cave walls.

The theory was accepted for some time, most notably by the French prehistorian Piette, but it gradually lost popularity as other ideas were proposed and nowadays few people support it. Perhaps the term "art" is not the most appropriate because it is clear to us that these paintings were not intended as such. Sometimes they are in places which are almost inaccessible or, at the very least, uncomfortable both for the artist and for those wishing to observe. It may be necessary to crawl along narrow galleries or even wade through water to get to the point. Sometimes the artist had so little room to work in, perspective is a real achievement as he literally could not stand back from his work.

2.Totemism

The first interpretation of Upper Paleolithic paintings, which ascribed them as being totemic, came about as a result of the work *Totemism by James Fraser. Essentially, totemism is the identification of Man with any particular animal, plant or object, therefore Man would have had a special relationship with those animals he chose to paint. Fraser's book explored tribes around the world that seemed to have totems and was principally a compilation of interviews and legends. The acceptance of this idea was great and it became the fashionable theory of its time. Many scholars went on to compare the Franco-Cantabrian paintings with others in Australia. Since the Aborigines had continued their traditional painting until shortly before the end of the nineteenth century, the key to the motives and meaning of the European cave paintings could be easily resolved as the answer might be in living memory.

*Frazer, Sir J.G. Totemism and Exogamy MacMillan(London)

3. Sympathetic magic

In 1903 S. Reinach, who had been a supporter of totemism, put forward the theory of sympathetic magic being the motive for the paleolithic paintings. Sympathetic magic is the idea that by representing some animal in a picture you could hold some kind of influence over it. He believed there were two variants of this sympathetic magic used for two separate basic purposes; hunting and fertility. In the first of these cases, he thought that the animals would have been painted before a hunting expedition to, in some way, ensure a good catch. Often we find painted on cave walls symbols which are even more mysterious than the figures. Reinach had a hunch that these signs might have a sexual significance but it was Henri Breuil, an eminent and prolific prehistorian, who expanded the idea based on new evidence and developed it further. He felt these symbols were painted to induce greater fertility, both of the animals hunted and of Man himself.

Reinach's idea of sympathetic magic was, and still is today, one of the most widely accepted ones due to a large extent to Breuil who then adopted and popularised it.

In 1923 more support came for the theory following Norbert Casteret's discovery in Montespan. In these caves in the French Pyrenees clay statues of animals were found, notably one of a bear that came to be known as the Montespan Bear. A bear skull and hide had seemingly been attached to the figure and this, as well as other statues of horses and a 1.5-metre-high lion, were full of holes as if they had been pierced with some kind of spear. This find appeared to reinforce the idea that some ritual was performed to propitiate hunting and Breuil was amongst its followers. However, as his career progressed he became more and more involved with documenting the paintings, considering the styles used and dating them and in fact, he grew reluctant to comment on interpretations as it was unclear exactly what ceremonies and rites might have been involved.

4. Composition

Following Breuil's death in 1961 the time was ripe for the emergence of new ideas and Andre Leroi-Gourhan began to question interpreting the meaning of individual paintings. Earlier, Breuil had noted that fierce animals were found painted in the deepest parts of caves and Leroi-Gourhan took this idea further by carrying out a comprehensive statistical study of which animals were painted and where they were located within the cave system, as detailed in the symposium on parietal art in Santander in 1970*. While his interpreting may be open to much debate, he made some very fine observations and the statistical information he laboriously collected has proved valuable for many subsequent investigations.

*Leroi-Gourhan, André "Considerations sur l'organisation spatiale des figures animales dans l'art pariétal paléolithique" Santander Symposium (Santander, 1972)

He divided the cave itself into panels, passages and niches and claimed that generally every animal has been allocated its own particular place and no other within the cave, establishing something like a pattern for the distribution of paintings. He established four different groups of animals and claimed that not all these groups would be painted in the same place but rather particular combinations of these. For example, the panels were mainly made up of bison (Group B) in the main part and horses (Group A) at the edges, in the galleries could be found horses (A) and deer (Group C), in the niches there were claviforms and other sexual signs and he confirmed Breuil's idea that only Group D animals, the fierce ones, (rhinos, felines and bears) were usually painted in the deepest and more remote parts of the cave. He went on to say that the horses were a representation of masculinity and bison were feminine, regardless of the gender they might appear to have in the painting.

Hence, he concluded, all the paintings and etchings were related with each other, each one just an element of the larger picture or composition. Thus, all the animal representations in any one cave would necessarily have been carried out within a relatively short period of time.

5. Shamanism

When Leroi-Gourhan died in 1986 prehistorians were again ready to consider new thoughts. One of these, as upheld by David Lewis-Williams, was that the Upper Paleolithic paintings were shamanistic art - images from a mind in a state of hallucination. He came to this conclusion after studying the San people of southern Africa and their art, some of which was still being created until very recently, a fact which enabled him to conduct interviews and witness shamans in trances and so on. He wondered if there could be a similar interpretation for the Franco-Cantabrian art and found the link he was looking for in the geometric signs that Leroi-Gourhan had attributed to gender. While studying the shamanistic trances of the Sans, he had discovered that in the first stage of hallucination the shaman would see geometric forms such as grids, dots and curves, in the second he would see objects and in the final third phase often human/animal chimera, known as therianthropes and which constitute an intriguing element of Upper Paleolithic art. His hypothesis goes on to claim that the shamans would often have perceived their hallucinations as emerging from the cave wall and in this way painting them would have been a way of touching and marking what had been put there by spirits.

VALIDITY OF THESE THEORIES

However, none of these theories are totally convincing. Some are more easily dismissed than others but even those which seem to be more tenable have been developed on the basis of comparison to primal cultures that have always been totally isolated from the European paleolithic Man. Just because two cultures are both primal it does not mean that they share the same values, knowledge and way of life. The Aborigines of Australia or tribes in Africa were completely different races whose customs, environment and life in general bore little ressemblance to that of those who are responsible for the Franco-Cantabrian paintings.

Data from Accelerator Mass Spectometry indicates that the paintings were done over a great period of time. It is generally admitted that this activity continued for anywhere between 6 and 10,000 years or even longer. As Paul Bahn* explains, this makes the idea of the paintings being a composition, as Leroi-Gourhan sustained, untenable and the belief that they are an accumulation much firmer. Moreover, it seems unlikely that one single ideal or belief would have survived unblemished and with no competition emerging over such an enormous period of time. During this same period new tools were developed, usually as a result of an interchange, pacific or otherwise, with other peoples. So if tools, which are bound by unchanging laws of physics were modified and improved, why not the spiritual or religious beliefs, which are not restricted by any physical conditions?

* Bahn, Paul G. "Lascaux: Composition or Accumulation?" Zephyrus Revista de Prehistoria y Arqueología. XLVII. Ed. Universidad Salamanca, 1994

SPIRITUALITY: THE CLUE FOR UNDERSTANDING Foundations of Man's spirituality

In fact it is this spirituality which we believe is fundamental to interpreting the Upper Paleolithic paintings. It seems to be often forgotten or ignored that primal people held very strong spiritual beliefs. Evidence from burial sites unearthed principally in present day Iran indicates that the Neanderthals, who existed before the race of man we are talking about here, believed in some kind of afterlife and therefore the idea of a soul or spirit existing within the body and leaving it after the physical death of this, is deeply rooted in the mind, what C.G.Jung describes as "archetypes of the collective unconscious". It should also be remembered that the idea of Man being superior to other animals with a divine right to use them in any way they see fit is fundamentally a Christian belief and that previous to this, in all hunter-gatherer cultures, Man held deep respect for them and the spirit or soul they thought all living things possessed.

The last European modern primal hunters

At the time of the paintings we are studying, the hunter-gatherer cultures that existed in Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia were by no means the same. They may have all been primal and shared common roots but these roots were so far in the past that their evolution inevitably varied in the three continents.

However, just some 200 years ago some peoples in North East Eurasia were still living in much the same way, with beliefs that apparently differed little and in a similar environment as the prehistoric man we are talking about. These tribes lived along the same latitude, from Siberia to some islands of Japan. In the most western region of these reaches in Central Siberia lived the Ostiaks along the Yenisey River. Further east near the Amoor River lived the Tunguzian peoples, the Gilyaks, the Gold] and the Orotchis. The Ainu or Aino people could be found on the Japanese island of Yezo, as well as in Saghalien and some of the Kurile Islands. Finally, the Koryak lived further north east. They were the bear and reindeer hunters of modem times, dependent on this prey to survive, and much of their way of life was recorded by explorers who came across them, principally the Reverend John Batchelor, as described in detail in "The Golden Bough " by James Fraser.

THE BEAR CULT

According to Batchelor's testimony, all these people, although inhabiting a huge expanse of land, lived in a similar way in the same kind of environment, hunting the bear for its meat. What is surprising though is the striking similarity in their hunting rituals. They all considered it necessary to perform lengthy ceremonies paying homage to the dead bear's spirit in order to deceive it or pacify its anger at having been disembodied. Although there were small differences in the rites, the essence of these and the concepts used were the same.

Practices common to these tribes

The following were all usual among these people:

1.The worshipping of the animal, often preceded by insults then excuses for participation in the killing and accusations of blame directed at other tribes or people.

2. The bear was skinned, often leaving the head attached to the hide, and this skin was sometimes donned by a dancer. Other times it was stuffed with straw to make it appear alive again, carried around the village and pierced with spears.

3. In most of the tribes there were specially designated members who would cook the meat of the dead bear in special pots reserved exclusively for this purpose and before being eaten,a portion would often be offered to the head of the dead animal in classic auto-feeding rituals.

4. The bones, particularly the skull and femurs, would usually be preserved in hidden places outside the village or sometimes buried under their huts.

Elementary foundations

The key to understanding this bear cult is well explained by Sir James Frazer when he says that,

The explanation of life by the theory of an indwelling and practically immortal soul is one which the savage does not confine to human beings but extends to the animate creation in general. In so doing he is more liberal and perhaps more logical than the civilised man, who commonly denies to animals that privilege of immortality which he claims for himself. The savage is not so proud; he commonly believes that animals are endowed with feelings and intelligence like those of men, and that, like men, they possess souls which survive the death of their bodies either to wander about as disembodied spirits or to be born again in animal form.*

Consequently, killing and eating animals was of much greater significance to these hunters than to us who consider them simply a source of food. As Frazer explains, "Hence on the principles of his rude philosophy the primitive hunter who slays an animal believes himself exposed to the vengeance either of its disembodied spirit or of all the other animals of the same species ".*

*Frazer, Sir James G. The Golden Bough Abridged edition MacMillan (London) 1925

Probable origins of the bear cult

The cult of the bear can be traced back to prehistoric times. The oldest known remains that show evidence of this are those discovered in the early part of the century in the high mountain grotto of Drachenloch, or the Dragon's Den, in Switzerland and they date back to the Mousterian era. Bear skulls and long bones were found, extremely well-preserved, inside cabinets made from slabs of stone. The fact that only particular bones and always the skull were chosen to be preserved suggests this was a bone-offering cult, common among Man living in northern Europe. In particular, there is a fine example of a bear skull with bones placed inside its mouth, presumably representing an auto-feeding ritual (Fig 1).

Despite the evidence, one prehistorian, Leroi-Gourhan, questioned the reliability of the records made at the time of the discovery claiming that the cabinets and so on must have been the work of Magdalenian Man since Neanderthal Man was too primal for this kind of behaviour. So intent was he to discredit Neanderthals, according to the thinking of his day, that he overlooked the fact that Magdalenian Man had not come into existence at the time the remains are dated and that, in any case, the cave-bear had died out before their appearance.

Evidence of bear cult in Western Europe

In 1923, a young amateur caver, Norbert Casteret, came across one of the most important finds in prehistory in Montespan in the French Pyrenees. Having heard of a flooded underground cavern his strong sense of exploration led him to crawl and swim through galleries and chambers, many of which were totally submerged in water, carrying wrapped matches and candles in his pockets. Finally his perseverance was rewarded with the discovery, in the deepest part of the cave, of the Montespan Bear, one of the oldest known sculptures in the world (some 20,000 years old). (Fig 2)

As well as this bear modelled in clay, there were almost thirty other sculpted figures, including a 1.5-metre-high lion, and tens of paintings and engravings on the walls of the chamber. Holes could be seen on the body of some of these animals, including the bear, as if they had been repeatedly stabbed at with a sharp object, like a spear. A bear skull was lying next to the model leading some experts to believe that the hide of the animal had been used to cover it, with the head attached to enhance the resemblance to a living bear. They claimed that a wooden pole may have been used to balance the head on, although this would probably have been unnecessary if it was still attached by the skin of the neck.

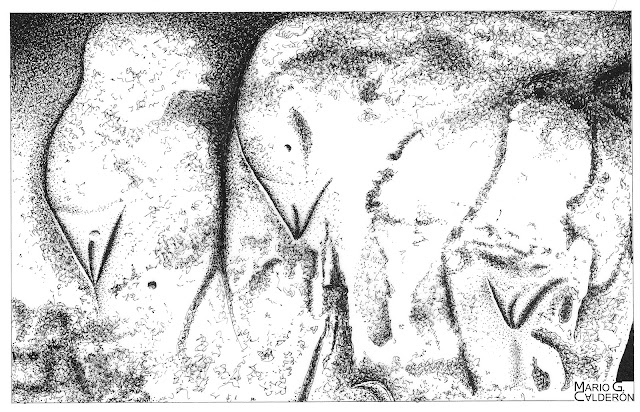

Montespan is not the only cave where sculptures have appeared. The cave of Tuc d'Audoubert, in the Ariège region of France is unique for the superbly sculpted bison found within.(Fig 3)

Like the Montespan Bear they

were found deep in the cave system and also made of clay, although these bison are thought to date from

some 5,000 years later..

There are two together leaning against rocks and although they are three dimensional only one side of each animal

has been carved. The scale is approximately one sixth of the real size and they are perfect in

form with a true sense of movement about them. They are remarkable given their antiquity and the limited

tools and techniques

available at that time. No remains of the instruments or tools they may have used have been found although some

small sausage-shaped pieces of clay can be seen on the cave floor. It was at first thought that

these were some kind of phallic representations but nowadays the belief if that they were samples used

to test the plasticity of

the clay. There are also some footprints as well as small, round grooves in the floor believed by some to be heel

prints of children because of their reduced size.(Fig

4)

Dating from approximately the same time Cap Blanc, in the Dordogne region of France, contains a similar bas relief carved in places up to 20 cm deep. The frieze covers 14 metres of the wall and includes bison, horses and cervids, often one on top of the other as we have seen in many of the painted panels.

Analysing the facts gathered from these sites it is easy to see that the bear cult practised there had much in common with that of the last known hunter-gatherers of the northern hemishere, those whose activities have been so meticulously recorded by scholars such as Bachelor, Dr B. Scheube and Leon Sternberg. The physical evidence shows us that both these nineteenth century tribes and the primal hunters of Montespan needed a representation of the bear to perform the rituals, and to make this as credible as possible the dead bear's hide was used, with the head still attached, and this was thrown over a person or model or stuffed with straw. We know the Siberian tribes insulted and would physically attack the bear representation and the lion in Montespan has clear signs of having been pierced with spears. The Montespan bear also shows evidence of this as we can see in one of the first photographs ever taken of it with the young Casteret at its side.(Fig 5) Although the holes left are less pronounced than those on the lion, we should remember that the bear would have been covered with a thick hide affording it some protection against spears.

Also in Montespan a horse engraved on the clay wall can be seen.(Fig 6)

This horse is covered in large round marks similar to those of the bear and lion and were probably made by throwing spears at it or simply making the marks to represent that idea. The resemblance of this horse to one which is painted in Pech Merle (Fig 7) is striking.

The motive behind the circular marks that have been made all over it and another one on the same wall must surely be the same. Another beautiful example is the engraved bison at Niaux (Fig 8).

Links between ancient and modern rituals

This inevitably begs the question, were their rituals the same and based on the same beliefs?

To answer this question we should consider the following facts:

a) up until the last hunter-gatherers known, there was a fundamental belief that both man and animals possess a spirit and neither is superior to the other

b) they felt sorrow and remorse after killing what they considered a fellow animal, even though this was necessary for their survival

c) they also experienced fear as they believed that the spirit deprived of its physical body would wander angrily and may try to take revenge thus posing a direct threat relative to its size and ferocity or indirectly by persuading its living counterparts to disappear, so thwarting Man's hunting possibilities

For these reasons then, Man believed it was necessary to pay homage to the dead animal and to appease its angry spirit, through some rituals.

Rituals surrounding the bear cult

Some 20,000 years ago hunters in Montespan, having successfully killed a bear, modelled a body from clay to provide a physical frame for the dead animal's spirit to reside in. Just as the Siberian tribes, these people would have both worshipped and hated the bear at the same time, hence the marks left by the spears. The model was located deep inside the cave in a place where it would not be disturbed by people since it was a dangerous animal that could do great harm. Likewise, no footprints or any other outward sign of those responsible for the model can be found nearby since they would have abandoned the cave as silently as possible, erasing all traces that might allow the spirit to come after them.

In Tuc d'Audoubert, about 5,000 years later the same kind of rites would have been performed centred round the bison modelled in clay. Some mystery surrounds the supposed children's heelprints leading away from the bison and amongst clear,larger footprints. If we accept they were made by children, due to their reduced size, were they allowed to play in such a sacred place? Many of those that maintain they were made by children claim they were performing some rite, some say of initiation, where they would have had to walk on their heels with the toes in the air.

Perhaps the imprints were left by the artists themselves as they backed away quietly from the bison where the spirit was now supposed to be. It would have been of utmost importance to them that they did not disturb the spirit as they were leaving, that as they did so they did not take their eyes off it as a precaution and that they left behind no recognisable tracks that could identify and locate them. Backing away on their heels then, the suction created as they lifted their heels out of the mud would have reduced the size of the marks left behind instantly.

The evidence from these two sites remains to this day but this practice of constructing a model bear would surely have been more commonplace. It is likely they made similar structures from frames made from branches and stuffed with dried grasses or reeds, all perishable materials and therefore long since disappeared.

TRANSITION TO PAINTING

Sculptures in caves are a rare find. What is much more common is paintings on walls of caves. Modern dating techniques indicate that the trend went from sculpture through bas-relief to finalise in the more abstract, and of course less time-consuming, two dimensional paintings. This evolution from the concrete to the abstract is common in the history of mankind and is perfectly reflected in the previous examples: the rough clay figure covered with the bear hide of Montespan, the more sophisticated carving of just one side of the bison in Tuc d'Audoubert and finally the more commonplace paintings which often deliberately utilised the uneven rock surface.

So most paintings and engravings done on walls or blocks of stone will be related to these spirit-dwelling rituals that were previously in the form of sculptures. With the passing of time the three dimensional figures covered in hide (like the Montespan Bear) were simplified to "half models" like the bison of Tuc d'Audoubert or the bas-reliefs of Cap Blanc. Then they began to paint and engrave on the wall of the cave where its cracks and bulges insinuated the shape of the animal they wanted to represent. Later, a flat wall surface or block of rock would have been sufficient for their two-dimensional paintings which sometimes they would shade to suggest the three dimensions. The paintings become more and more simplified and abstract until finally they seem to only do engravings.

Although this seems to be a logical chronology, some evidence contradicts it. It is not that simple, as forms that are the most abstract are not always the most modern and some engravings appear to be older than some of the paintings. In spite of the fact that it seems any support for the spirit was sufficient to perform its function, on special occasions or depending on the availability of skilled artists, a more detailed and better quality image could be achieved, thus giving them more satisfaction in their handiwork. On the whole, though, it is not the way the painting looks which is important so much as the results obtained from having represented the animal as, for example, in many panels we can see where they have painted over drawings already existing or modified them making use of some of the lines. In doing so, earlier images would often be spoiled or erased, but as they did not consider this '`artwork" then this was not taken into consideration. What they were doing was providing a kind of virtual body for the spirit of the dead animal to reside in. In this way they achieved several goals;

1. The spirit of the (sometimes dangerous) hunted animal would not be able to seek revenge on its slayers if it was trapped in the picture

2. For the same reason, this spirit could not tell its living counterparts who the culprits had been, which would have lead them to perhaps disappear from the area

3. By doing the painting in a deep unused part of the cave (Group D animals according to Leroi-Gourhan's classification)they could keep spirits of dangerous animals at a safe distance from them

It is important to note that these rituals were performed after the hunt and not before. So the paintings were not intended to propitiate immediate hunting but rather to ensure future kills would not be prejudiced as a result of the slaying of this animal.

PAINTINGS OTHER THAN ANIMALS

If we admit this theory, then what about the figures which seem to be semi-humanlike the one at the centre of the panel in the sanctuary of Les Trois Freres (Fig.9),

another in a different chamber (Fig 10)

or the one in Gabillou? (Fig. 11)

Or the dots, lines and other signs? Or the hand silhouettes?

Therianthropic figures

Looking at these strange animals in human stances we are once again reminded of Fraser's account of the Ostiaks and other tribes. He describes how often a member of the community would don the hide and head of the slain animal and dance around. The object of this was to convince the disembodied spirit that the animal was still alive and thus it could be persuaded to inhabit the body. The strange "semi-human" creatures are probably simply a representation of this ritual.

Abstract signs

The abstract signs that can be found in many caves have confounded experts since their discovery and will continue to do so. There are, for example, dots, grids and nets. It is almost impossible to determine what these may have represented although some claim the grids may be traps or snares for hunting animals or some kind of map. The dots defy explanation as the possibilities of their interpretation are countless and while some of the lines resemble feathers, baskets or some other thing any interpretation would be on very shaky ground. Some of the signs are widespread, like the ubiquitous dots or simple straight lines although the more complex ones only appear in any one particular area and so would probably only be known locally. "El Castillo" cave in northern Spain has many examples of these kind of signs (Fig 12 )that appear in no other place, except, in some cases, in the nearby Altamira cave.

Sexuality and reproduction

Some signs seem to be more clearly identifiable and, for example, refer to gender or may record aspects of their life. The clearest examples of the so-called painted bell shapes occur in El Castillo and are generally accepted to represent female sexuality as they seem to be a clear representation of a woman's genitalia (Fig 13).

Perhaps, then, they were painted to increase fertility within the tribe. Other signs are clear line representations of a woman, either painted or engraved, and appear in numerous caves. Sometimes a large section of the female figure can be seen like those in Angles-sur‑

Anglin that show from above the waist (including a prominent belly and even navel) to the thighs (Fig 14)and other times a simpler version like in the Dordogne.

There are other painted or engraved symbols which are always a vertical line with varying degrees of bulges (one or two)(Fig.15).

They can easily be compared to similar shapes in mobile art (Fig 16) which clearly are of the female

form and are known as claviform figures. These sylised silhouettes and figures are

sometimes so schematic it would have been difficult to identify them were it not for the

fact they can be compared to the more complete

ones.

Cave as womb

There is a great abundance of references to the female sex right across central and western Europe. These representations in the former tend to be in mobile art and in the latter it is more common to find paintings and engravings. The small dark opening on a mountainside (the cave opening) may have been interpreted as a vagina and the galleries leading into chambers only reinforces this parallel by ressembling the inside of a female body. To primal man, to enter the cave would have represented penetrating the land itself In El Linar cave in northern Spain, a natural elongated gap in a side gallery has even had horizontal lines engraved around it to make it look more like a vagina. In La Pasiega (again in Cantabria, northern Spain) one of the claviform figures mentioned above has been painted in red next to the entrance of two corridors, which have an extremely suggestive appearance.

So perhaps the intention of those responsible was either to increase fertility or ease the process of giving birth. The fact that there is no truly reliable evidence of any kind of representation of mate sexuality in these caves (the interpretation of the barbed sign in El Castillo as a penis seems an extremely free and uncorroborated one) seems to reinforce the idea that the cave was considered female or, more precisely, the womb of the earth.

Some paintings of animals in caves may well have been done there in the belief they were placing them in the very womb of the land. These paintings are normally on the walls of a chamber with no apparent exit situated at the end of a small gallery. They are simpler than others, appearing more primal, prior to Magdalenian.The function would have been to improve the fertility of the animals they hunted, either simply to provide more animals for them to hunt or to replace those they had killed. The caves then, were thought to have the power of generating new life.

Hand silhouettes

The silhouettes of hands which often appear on cave walls throughout France and Spain are very widespread and appear to be one of the oldest forms of painting (Gravetian and Aurignacian). Some caves are full of hands like Gargas, in the French Pyrenees, while in others they are far less numerous and all are red (iron oxide) or black (manganese oxide or charcoal). They do not seem to always appear in any one special part of a cave although usually if they exist they are mostly on the same section of wall.

The mark of a hand was done either by dirtying the palm or putting it in paint and then simply placing it on the wall or, more commonly, by holding the hand against the surface and blowing the paint at it directly from the mouth or using some kind of tube. Left hands are more common than right, (presuming the palm was placed facing the rock) perhaps because they were right-handed and so used the right hand to hold the tube and on many there are fingers missing or incomplete.

It has been said that they did this to mark territory or as a testimony to their presence there. Territorial markings, however, are not made in places where they are hidden from view but rather, quite the contrary, they should be clearly visible as they are meant as a sign or warning. Others have claimed it was a form of offering themselves up to some deity or that this gave testimony to participation in some ceremony.

Since they are so common over such a wide area they most probably have a universal meaning. The fact that so many of the hands show incomplete fingers must be significant although some believe that this is simply a result of accidents while making tools and so on. This seems unlikely as an accident may misshape the finger or cause cuts and bruises but relatively seldom results in its total or partial loss.

For such a spiritual people, who were known to bury their dead and made such elaborate ceremonies for animals, is it not strange that there is no evidence of rituals related to their deceased? Perhaps the painting of a hand was to express their mourning to the spirit of their dead loved one. In those times, and even today in remote areas like the Philippines or Easter Islands caves were and are considered the dwelling places of spirits, whose influence is to be feared. It seems quite probable that they left these marks of hands in the caves to pacify the spirits of those who had passed on.

There were some tribes in Canada, whose members according to evidence from the nineteenth century, nearly all suffered finger amputation to one degree or another and usually of the left hand. The reason for this was that they cut their fingers when a close family member died in order to grieve. Perhaps emotional pain did not constitute a motive for crying in their culture and they somehow needed physical pain to express those feelings or maybe they were proving to others how much pain they felt inside by inflicting these wounds on themselves. Perhaps the same idea lies behind these very primal handprints.

While the exact significance is unclear, it seems probable to us that the handprints are connected with some kind of ritual performed when a member of the tribe died since, as yet, no other evidence has been ascribed to this. It is almost certain that some kind of ceremony would have taken place as there is evidence of more or less elaborate funerals from well before the Magdalenian period.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion we believe that the Franco-Cantabrian paintings should be analysed bearing in mind there must have been a practical purpose behind them, but that they were not all painted for the same reason. Some paintings are difficult to ascribe one or another function while others may not even be from the Paleolithic period, but the later Neolithic. Paintings where non-organic substances were used cannot be dated with any degree of reliability using present-day technology, and so age is estimated by comparing the style with others which have been reliably dated. However, we believe that they can be basically divided in three groups.

A. First we have those drawings related to spirit dwelling. These consist of animals and therianthropic figures (those creatures which seem to be part animal part human and in fact, as previously pointed out, were probably someone covered with the dead animal's hide). Those animals that belong to Leroi-Gourhan's Group A, B and C are most typically found in panels and have often been erased, painted over or modified since the provision of a new frame for the spirit to inhabit was the important thing, while the style or aesthetics of the painting itself was merely a secondary concern (Trois Freres and Lascaux, France or Altamira and Tito Bustillo, Spain). They are often painted or engraved on uneven rock surface where the grooves, cracks or protuberances of the rock itself make up part of the animal represented (Altamira and El Castillo, Spain). However, it is not only those in panels that refer to this idea of a frame for the spirit, but also the pictures and sculptures of ferocious, or Group D, animals that usually appear deep inside the cave system (Montespan, Tuc d'Audouvert in France). The clearest therianthropic figures are to be found in Le Gabillou and Trois Freres.

The last living people to practise rituals which could be an echo of those performed by Paleolithic Man were those tribes living in north east Asia in the nineteenth century as described by Batchelor and others. As the Ice Age drew to a close at the end of the Magdalenian period, tribes who hunted animals that typically lived in very cold climates like reindeer and bears,had to move further north following their prey. They would have taken their customs with them and these would have remained intact for a long time due to the isolation the terrain implied.

B. Secondly there are those paintings whose meaning is clearly related to sex and reproduction. There are complete (though usually faceless) figures of women (the carvings in La Madeleine, France), very clear etchings of the female pelvis (Angles-sur I'Anglin), symbols which clearly elude to the vagina (Dordogne and El Castillo) and stylised silhouettes of women (Peck-Merle, La Roche, Les Combarelles, Niaux in France and Pindal, Spain). All of these, then,would have been painted to aid fertility and childbirth and were done in the "womb of the earth" for greater effect. A number of paintings of animals which were important in their diet and posed no physical threat to them found in small roundish chambers (classified by Leroi-Gourhan as "diverticule" or niche animals) may well have been painted here for similar reasons, that is to say to ensure their reproduction.

The cradle for this culture of the female sex is Central Europe where the earliest examples (in mobile art) have been discovered from the Gravettian period. Carved figures of Venuses become steadily more scarce as we move westwards, until we arrive in Spain where they are almost absent.

C. Finally there are those paintings or symbols that do not apparently belong in either of these two groups and which are difficult to classify. Many of these only appear in any one particular cave and so would have a very local meaning (El Castillo) while others, like the large dots are more commonly found. The meaning of strictly local signs is extremely unlikely to have survived to recent times while those which are universal may have had different interpretations depending on where they are found and the era they were made.It should also be borne in mind that some of these are engraved or in iron oxide, thus making dating them very unreliable. If they belong to a later period than the Paleolithic, perhaps the Neolithic or Bronze Age, for example, the possibility for interpretations multiplies.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am most grateful to Karen Chapman for her invaluable linguistic contribution to this paper and to Mario Gómez Calderón for his magnificent illustrations.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alcalde del Rio, H., Breuil, H. & Sierra, L. : Les cavernes de la région cantabrique. Monaco, Imprimerie Vve. A. Chêne 1911

Altuna, J. & Apellániz, J.M. : Las pinturas rupestres paleoliticas de la Cueva de Ekain (Deva, Guipúzcoa) Munibe, 1-3 1978

Bahn, P. : Lascaux: Composition or accumulation? ZEPHYRVS Revista de Prehistoric y Arqueologia XLVII, 1994

Balbin Behrmann, R..: L 'art de la grotto de Tito Bustillo (Ribadesella). Une vision de synthése in L'Anthropolgie, 93-2 1989

Balbin Behrmann, R. & Gonzalez Sainz, C. : Las pinturas y grabados paleoliticos del corredor B7 de la cueva de La Pasiega (Cantabria). "El hombre fósil" 80 años después. Univ. Cantabria, Fundación Marcelino Botín. Asturias 1996,

Balbin Behrmann, R. & Moure Romanillo, A. : La galeria de los caballos de la cueva de Tito Bustillo in Altamira Symposium, Madrid, Ministerio de Cultura 1980

Balbin Behrmann, R. & Moure Romanillo, A. : Las superposiciones en el panel principal de la cueva de Tito Bustillo in Homenaje al Prof Dr. Martin Almagro Basch, I. Madrid, Ministerio de Cultura 1983

Bandi, H.G. : L'art préistorique. Paris 1955.

Barandiarán Maestu, I. : Arte mueble del Paleolítico Cantábrico. Univ. de Zaragoza, Zaragoza 1973

Bataille, G. Lascaux, or The Birth of Art. Lausanne 1955.

Baudet, J.L. Les figures anthropomorphes de l'Art rupestre de I'Île de France. La Societe d'Anthropologie (Paris) : Bulletin et mémoires II, Ser. 10 (Fast. 1-3), 1950-52.

Baudet, U. : Les Peintures et gravures rupestres del'Île de France. Cong. prehist. XIII, Paris 1950 : Compte Rendu. Paris 1950,

Bégouën, H. : Les Bisons d'argile de la caverne du Tuc d'Audoubert (Ariège). Academia des inscriptions et belles-lettres : Comptes rendus. Paris 1912.

Bégouën, H. : Dessins inédits de la Grotto de Niaux (Ariège). Ipek, Berlin I-III, 1934,

Bégouën, H., Breuil, H. : De quelques figures hybrides (mi-humaines, mi-animales) de la caverne des Trois-Frères (Ariège). Revue anthropologique (Paris) XLIV, 1934.

Beltran, A. : Las vulvas y otros signos rojos de la cueva de Tito Bustillo (Ardines, Ribadesella, Asturias) Santander Symposium. Santander 1972

Berenguer Alonso, M. : El arte parietal prehistórico de la cueva de Llonin in Boletín del Instituto de Estudios Asturianos, 105-106 1982

Bourdier, F. : A propos de l'art schématique du paléolithique. Bull. Soc. préhist. LV, 1958

Breuil, H. : Les Peintures rupestres schématiques de la peninsula Ibérique. 4 vol. Lagny-sur-Marne 1933-35

Breuil, H. : Les Peintures et gravures par0ales de la Caverne de Niaux (Ariège). Bulletin de la Societe préhistorique de l'Ariège V, 1950

Breuil, H. : Quatre cents siecles d'art parietal. Montignac 1952

Breuil, H., Obermaier, H. : The cave of Altamira at Santillana del Mar. Madrid 1935 Cam6n Aznar, J. : Las artes y los pueblos de la España primitive. Espasa-Calpe, Madrid 1954

Cartailhac & Breuil : Les Peintures et gravures murales des cavernes pyrénénnes IV Gargas, Cme Aventignan (Hautes-Pyrérées) 1910

Drouot, E.: L'art paléolithique a la Baume-Latrone, Cahiers Ligures de préhistoire et de I'archéologie (Montpelier) II. 1953

Gonzalez Sainz, C., Munoz Fernandez, E. & San Miguel Llamosas, C.: Los grabados rupestres paleoliticos de la cueva del Otero (Secadura, Cantabria) in Sautuola, IV 1985

Laming-Emperaire, A. La signification de I'art rupestre paleolithique. Paris 1962 Laming-Emperaire, A. Art Rupestre et Organisation socials. Santander Symposium. Santander 1972

Lemozi, A. La Grotte-Temple de Pech-Merle. Paris 1937

Lemozi, A. Les Figurations humaines préhistoriques dans la région de Cabrerets (Lot.) Congrès Préhistorique de France, Paris 1937

Leroi-Gourhan, A. Hommes de la prehistoire. Les chasseurs. Paris 1955

Leroi-Gourhan, A. (a) La fonction des signes dans les sanctuaires paleolithiques. (b) Le symbolisme des grands signes dans l'art parietal paleolithique. (c) Répartition et groupement des animaux dans l'art parietal paleolithique. Bull. Soc. préhist. LV (a: Fasc. 5-6, b: Fasc. 7-8, c: Fasc. 9) 1957-1958

Leroi-Gourhan, A. : Les signes parietaux comme "marqueurs " etniques in Altamira Symposium, Madrid, Ministerio de Culture 1980

Leroi-Gourhan, A. : Los primeros artistas de Europa. Introducción al arte paleolitico. Madrid, Ediciones Encuentro 1983

Leroi-Gourhan, A.: Préhistoire de l'art occidental. Paris 1965

Lorbranchet, M. : Datation des peintures parietales paleolithiques in Le temps de la Prehistoire, I J.P. Mohen), Paris, Soc. Préhistorique Française 1989

Moure Romanillo, A. Composition et variabilité dans l'art parietal paleolithique Cantabrique in L'Anthropolgie, 92-1., 1988

Moure Romanillo, A. & Bernaldo de Quirós, F. : Altamira et Tito Bgustillo. Reflexion Sur la chronologie delart polychrome de la Fin de Paleolithique Supérieur in L'Anthropolgie, 100-2. 1995,

Moure Romanillo, A., Gonzalez Sainz, C., Bernaldo de Quirós, F. & Cabrera Valdes, V.: Dataciones absolutes de pigmentos en Cuevas can0bricas: Altamira, El Castillo, Chimeneas y Las Monedas. Univ. Cantabria, Fundaci6n Marceline Botin. Asturias 1996.

Múzquiz, M. : El pintor de Altamira pinto en la cueva de El Castillo in Revista de Arqueologia, 114. 1990.

Nougier, L. : Nouvelles approches de l'art préhistorique animalier. Santander Symposium. Santander 1972

Roussot, A. : Contribution a l'étude de la frise parietals du Cap Blanc. Santander Symposium, Santander 1972

San Miguel Llamosas, C. : El conjunto de arte rupestre paleolitico de la cueva del Liner (Alfoz de Lloredo, Cantabria) in XX Congreso Nacional de Arqueologia (Santander, 1989) Zaragoza 1991

Sieveking, A.: Style and regional grouping in Magdalenian cave art in Trabajos de Prehistoria,35. 1979

Ucko, P. & Rosenfeld, A. : Anthropomorphic representations in palaeolithic art. Santander Symposium. Santander 1972

Ucko, P. & Rosenfeld, A. : Arte paleolitico B. H. A. Madrid 1967

Züchner, C. : The scaliform sign of Altamira and the origin of maps in prehistoric Europe. Univ. Cantabria, Fundación Marceline Botin. Asturias 1996.

Author : Rafael Menéndez García

INTRODUCTION

When we talk about art in caves, the first thing we usually think of are the images of bison painted on the walls and celings of caves, particularly those in Altamira in Northern Spain, or bulls and horses found in Lascaux, in the south of France. Indeed, the region stretching between and around these two points is where the greatest abundance of this kind of art can be found; at least 200 caves featuring paintings or engravings on the walls and, less commonly, sculptures. There is little variation in terms of subject matter, style and conception between cave paintings found in this area and they are so homogenous that the Franco-Cantabrian style has been established.

What is generally accepted to be the earliest form of painting in caves which remains to this day are handprints, probably dating from the end of the Aurignacian period or the beginning of the Solutrean. This latter period seems to have seen the appearance of paintings deep inside the cave and more importantly, large carvings in bas-relief which are principally found in France. It was in the next period, the Magdalenian, that cave painting truly thrived, reaching its zenith in terms of quality in the early part of this timespan. In fact, the Magdalenian makes up some 80% of all cave paintings discovered.

Apparently, there were some parts of the caves more in demand by the painters, where we can find a mass of images painted using different techniques, with a different orientation and on a different scale. In these scenes, or panels, the animals overlap each other constantly in an apparent attempt to make as much use as possible of the space provided and strokes or basic shapes made by a previous painter may be taken advantage of by another to create a new animal. Sometimes, it would seem that the original painting has been rubbed out to make room for the new, as we can still make out the remains of paint on the wall. On the other hand, we can also find single paintings in a remote part of the cave, totally hidden from view. A flat surface was not always used. Quite the contrary, in fact, as often protuberances or rougher areas of the surface seem to have suggested the shape of the animal to the painter and in these cases this uneven surface, a crack or hole in the rock and even the shadow projected was usually incorporated into the image.

PREVIOUS INTERPRETATIONS

Bearing all this in mind, we should ask ourselves if the paintings were, in fact, meant to be viewed by anyone at all. Was it the intention of the painters to create what we call art? Were they seeking the admiration of their fellow man, or indeed of generations to come? Were they trying to leave their mark for posterity? We think it is time to take a fresh look at cave paintings but first we will summarise the theories that have aready been proposed as follows:

1. Art for art's sake

The idea of art for art's sake was the first, proposed as long ago as 1864 by Lartet and Christy, who claimed that as a result of abundant hunting and hence economic prosperity, Man was left with so much free time that he entertained himself decorating tools, weapons and cave walls.

The theory was accepted for some time, most notably by the French prehistorian Piette, but it gradually lost popularity as other ideas were proposed and nowadays few people support it. Perhaps the term "art" is not the most appropriate because it is clear to us that these paintings were not intended as such. Sometimes they are in places which are almost inaccessible or, at the very least, uncomfortable both for the artist and for those wishing to observe. It may be necessary to crawl along narrow galleries or even wade through water to get to the point. Sometimes the artist had so little room to work in, perspective is a real achievement as he literally could not stand back from his work.

2.Totemism

The first interpretation of Upper Paleolithic paintings, which ascribed them as being totemic, came about as a result of the work *Totemism by James Fraser. Essentially, totemism is the identification of Man with any particular animal, plant or object, therefore Man would have had a special relationship with those animals he chose to paint. Fraser's book explored tribes around the world that seemed to have totems and was principally a compilation of interviews and legends. The acceptance of this idea was great and it became the fashionable theory of its time. Many scholars went on to compare the Franco-Cantabrian paintings with others in Australia. Since the Aborigines had continued their traditional painting until shortly before the end of the nineteenth century, the key to the motives and meaning of the European cave paintings could be easily resolved as the answer might be in living memory.

*Frazer, Sir J.G. Totemism and Exogamy MacMillan(London)

3. Sympathetic magic

In 1903 S. Reinach, who had been a supporter of totemism, put forward the theory of sympathetic magic being the motive for the paleolithic paintings. Sympathetic magic is the idea that by representing some animal in a picture you could hold some kind of influence over it. He believed there were two variants of this sympathetic magic used for two separate basic purposes; hunting and fertility. In the first of these cases, he thought that the animals would have been painted before a hunting expedition to, in some way, ensure a good catch. Often we find painted on cave walls symbols which are even more mysterious than the figures. Reinach had a hunch that these signs might have a sexual significance but it was Henri Breuil, an eminent and prolific prehistorian, who expanded the idea based on new evidence and developed it further. He felt these symbols were painted to induce greater fertility, both of the animals hunted and of Man himself.

Reinach's idea of sympathetic magic was, and still is today, one of the most widely accepted ones due to a large extent to Breuil who then adopted and popularised it.

In 1923 more support came for the theory following Norbert Casteret's discovery in Montespan. In these caves in the French Pyrenees clay statues of animals were found, notably one of a bear that came to be known as the Montespan Bear. A bear skull and hide had seemingly been attached to the figure and this, as well as other statues of horses and a 1.5-metre-high lion, were full of holes as if they had been pierced with some kind of spear. This find appeared to reinforce the idea that some ritual was performed to propitiate hunting and Breuil was amongst its followers. However, as his career progressed he became more and more involved with documenting the paintings, considering the styles used and dating them and in fact, he grew reluctant to comment on interpretations as it was unclear exactly what ceremonies and rites might have been involved.

4. Composition

Following Breuil's death in 1961 the time was ripe for the emergence of new ideas and Andre Leroi-Gourhan began to question interpreting the meaning of individual paintings. Earlier, Breuil had noted that fierce animals were found painted in the deepest parts of caves and Leroi-Gourhan took this idea further by carrying out a comprehensive statistical study of which animals were painted and where they were located within the cave system, as detailed in the symposium on parietal art in Santander in 1970*. While his interpreting may be open to much debate, he made some very fine observations and the statistical information he laboriously collected has proved valuable for many subsequent investigations.

*Leroi-Gourhan, André "Considerations sur l'organisation spatiale des figures animales dans l'art pariétal paléolithique" Santander Symposium (Santander, 1972)

He divided the cave itself into panels, passages and niches and claimed that generally every animal has been allocated its own particular place and no other within the cave, establishing something like a pattern for the distribution of paintings. He established four different groups of animals and claimed that not all these groups would be painted in the same place but rather particular combinations of these. For example, the panels were mainly made up of bison (Group B) in the main part and horses (Group A) at the edges, in the galleries could be found horses (A) and deer (Group C), in the niches there were claviforms and other sexual signs and he confirmed Breuil's idea that only Group D animals, the fierce ones, (rhinos, felines and bears) were usually painted in the deepest and more remote parts of the cave. He went on to say that the horses were a representation of masculinity and bison were feminine, regardless of the gender they might appear to have in the painting.

Hence, he concluded, all the paintings and etchings were related with each other, each one just an element of the larger picture or composition. Thus, all the animal representations in any one cave would necessarily have been carried out within a relatively short period of time.

5. Shamanism

When Leroi-Gourhan died in 1986 prehistorians were again ready to consider new thoughts. One of these, as upheld by David Lewis-Williams, was that the Upper Paleolithic paintings were shamanistic art - images from a mind in a state of hallucination. He came to this conclusion after studying the San people of southern Africa and their art, some of which was still being created until very recently, a fact which enabled him to conduct interviews and witness shamans in trances and so on. He wondered if there could be a similar interpretation for the Franco-Cantabrian art and found the link he was looking for in the geometric signs that Leroi-Gourhan had attributed to gender. While studying the shamanistic trances of the Sans, he had discovered that in the first stage of hallucination the shaman would see geometric forms such as grids, dots and curves, in the second he would see objects and in the final third phase often human/animal chimera, known as therianthropes and which constitute an intriguing element of Upper Paleolithic art. His hypothesis goes on to claim that the shamans would often have perceived their hallucinations as emerging from the cave wall and in this way painting them would have been a way of touching and marking what had been put there by spirits.

VALIDITY OF THESE THEORIES

However, none of these theories are totally convincing. Some are more easily dismissed than others but even those which seem to be more tenable have been developed on the basis of comparison to primal cultures that have always been totally isolated from the European paleolithic Man. Just because two cultures are both primal it does not mean that they share the same values, knowledge and way of life. The Aborigines of Australia or tribes in Africa were completely different races whose customs, environment and life in general bore little ressemblance to that of those who are responsible for the Franco-Cantabrian paintings.

Data from Accelerator Mass Spectometry indicates that the paintings were done over a great period of time. It is generally admitted that this activity continued for anywhere between 6 and 10,000 years or even longer. As Paul Bahn* explains, this makes the idea of the paintings being a composition, as Leroi-Gourhan sustained, untenable and the belief that they are an accumulation much firmer. Moreover, it seems unlikely that one single ideal or belief would have survived unblemished and with no competition emerging over such an enormous period of time. During this same period new tools were developed, usually as a result of an interchange, pacific or otherwise, with other peoples. So if tools, which are bound by unchanging laws of physics were modified and improved, why not the spiritual or religious beliefs, which are not restricted by any physical conditions?

* Bahn, Paul G. "Lascaux: Composition or Accumulation?" Zephyrus Revista de Prehistoria y Arqueología. XLVII. Ed. Universidad Salamanca, 1994

SPIRITUALITY: THE CLUE FOR UNDERSTANDING Foundations of Man's spirituality

In fact it is this spirituality which we believe is fundamental to interpreting the Upper Paleolithic paintings. It seems to be often forgotten or ignored that primal people held very strong spiritual beliefs. Evidence from burial sites unearthed principally in present day Iran indicates that the Neanderthals, who existed before the race of man we are talking about here, believed in some kind of afterlife and therefore the idea of a soul or spirit existing within the body and leaving it after the physical death of this, is deeply rooted in the mind, what C.G.Jung describes as "archetypes of the collective unconscious". It should also be remembered that the idea of Man being superior to other animals with a divine right to use them in any way they see fit is fundamentally a Christian belief and that previous to this, in all hunter-gatherer cultures, Man held deep respect for them and the spirit or soul they thought all living things possessed.

The last European modern primal hunters

At the time of the paintings we are studying, the hunter-gatherer cultures that existed in Europe, Africa, Asia and Australia were by no means the same. They may have all been primal and shared common roots but these roots were so far in the past that their evolution inevitably varied in the three continents.

However, just some 200 years ago some peoples in North East Eurasia were still living in much the same way, with beliefs that apparently differed little and in a similar environment as the prehistoric man we are talking about. These tribes lived along the same latitude, from Siberia to some islands of Japan. In the most western region of these reaches in Central Siberia lived the Ostiaks along the Yenisey River. Further east near the Amoor River lived the Tunguzian peoples, the Gilyaks, the Gold] and the Orotchis. The Ainu or Aino people could be found on the Japanese island of Yezo, as well as in Saghalien and some of the Kurile Islands. Finally, the Koryak lived further north east. They were the bear and reindeer hunters of modem times, dependent on this prey to survive, and much of their way of life was recorded by explorers who came across them, principally the Reverend John Batchelor, as described in detail in "The Golden Bough " by James Fraser.

THE BEAR CULT

According to Batchelor's testimony, all these people, although inhabiting a huge expanse of land, lived in a similar way in the same kind of environment, hunting the bear for its meat. What is surprising though is the striking similarity in their hunting rituals. They all considered it necessary to perform lengthy ceremonies paying homage to the dead bear's spirit in order to deceive it or pacify its anger at having been disembodied. Although there were small differences in the rites, the essence of these and the concepts used were the same.

Practices common to these tribes

The following were all usual among these people:

1.The worshipping of the animal, often preceded by insults then excuses for participation in the killing and accusations of blame directed at other tribes or people.

2. The bear was skinned, often leaving the head attached to the hide, and this skin was sometimes donned by a dancer. Other times it was stuffed with straw to make it appear alive again, carried around the village and pierced with spears.

3. In most of the tribes there were specially designated members who would cook the meat of the dead bear in special pots reserved exclusively for this purpose and before being eaten,a portion would often be offered to the head of the dead animal in classic auto-feeding rituals.

4. The bones, particularly the skull and femurs, would usually be preserved in hidden places outside the village or sometimes buried under their huts.

Elementary foundations

The key to understanding this bear cult is well explained by Sir James Frazer when he says that,

The explanation of life by the theory of an indwelling and practically immortal soul is one which the savage does not confine to human beings but extends to the animate creation in general. In so doing he is more liberal and perhaps more logical than the civilised man, who commonly denies to animals that privilege of immortality which he claims for himself. The savage is not so proud; he commonly believes that animals are endowed with feelings and intelligence like those of men, and that, like men, they possess souls which survive the death of their bodies either to wander about as disembodied spirits or to be born again in animal form.*

Consequently, killing and eating animals was of much greater significance to these hunters than to us who consider them simply a source of food. As Frazer explains, "Hence on the principles of his rude philosophy the primitive hunter who slays an animal believes himself exposed to the vengeance either of its disembodied spirit or of all the other animals of the same species ".*

*Frazer, Sir James G. The Golden Bough Abridged edition MacMillan (London) 1925

Probable origins of the bear cult

The cult of the bear can be traced back to prehistoric times. The oldest known remains that show evidence of this are those discovered in the early part of the century in the high mountain grotto of Drachenloch, or the Dragon's Den, in Switzerland and they date back to the Mousterian era. Bear skulls and long bones were found, extremely well-preserved, inside cabinets made from slabs of stone. The fact that only particular bones and always the skull were chosen to be preserved suggests this was a bone-offering cult, common among Man living in northern Europe. In particular, there is a fine example of a bear skull with bones placed inside its mouth, presumably representing an auto-feeding ritual (Fig 1).

|

| Fig. 1. A cave-bear skull with a longbone placed in the mouth. Drachenloch, Switzerland. |

Despite the evidence, one prehistorian, Leroi-Gourhan, questioned the reliability of the records made at the time of the discovery claiming that the cabinets and so on must have been the work of Magdalenian Man since Neanderthal Man was too primal for this kind of behaviour. So intent was he to discredit Neanderthals, according to the thinking of his day, that he overlooked the fact that Magdalenian Man had not come into existence at the time the remains are dated and that, in any case, the cave-bear had died out before their appearance.

Evidence of bear cult in Western Europe

In 1923, a young amateur caver, Norbert Casteret, came across one of the most important finds in prehistory in Montespan in the French Pyrenees. Having heard of a flooded underground cavern his strong sense of exploration led him to crawl and swim through galleries and chambers, many of which were totally submerged in water, carrying wrapped matches and candles in his pockets. Finally his perseverance was rewarded with the discovery, in the deepest part of the cave, of the Montespan Bear, one of the oldest known sculptures in the world (some 20,000 years old). (Fig 2)

|

Fig. 2. Clay figure representing a bear found by Casteret in Montespan.

|

As well as this bear modelled in clay, there were almost thirty other sculpted figures, including a 1.5-metre-high lion, and tens of paintings and engravings on the walls of the chamber. Holes could be seen on the body of some of these animals, including the bear, as if they had been repeatedly stabbed at with a sharp object, like a spear. A bear skull was lying next to the model leading some experts to believe that the hide of the animal had been used to cover it, with the head attached to enhance the resemblance to a living bear. They claimed that a wooden pole may have been used to balance the head on, although this would probably have been unnecessary if it was still attached by the skin of the neck.

Montespan is not the only cave where sculptures have appeared. The cave of Tuc d'Audoubert, in the Ariège region of France is unique for the superbly sculpted bison found within.(Fig 3)

|

Fig. 3. The clay bison found at Tuc d'Audoubert, Ariège.

|

|

| Fig. 4. Footprints around the bison sculpture in Tuc d'Audoubert. |

Dating from approximately the same time Cap Blanc, in the Dordogne region of France, contains a similar bas relief carved in places up to 20 cm deep. The frieze covers 14 metres of the wall and includes bison, horses and cervids, often one on top of the other as we have seen in many of the painted panels.

Analysing the facts gathered from these sites it is easy to see that the bear cult practised there had much in common with that of the last known hunter-gatherers of the northern hemishere, those whose activities have been so meticulously recorded by scholars such as Bachelor, Dr B. Scheube and Leon Sternberg. The physical evidence shows us that both these nineteenth century tribes and the primal hunters of Montespan needed a representation of the bear to perform the rituals, and to make this as credible as possible the dead bear's hide was used, with the head still attached, and this was thrown over a person or model or stuffed with straw. We know the Siberian tribes insulted and would physically attack the bear representation and the lion in Montespan has clear signs of having been pierced with spears. The Montespan bear also shows evidence of this as we can see in one of the first photographs ever taken of it with the young Casteret at its side.(Fig 5) Although the holes left are less pronounced than those on the lion, we should remember that the bear would have been covered with a thick hide affording it some protection against spears.

|

| Fig. 5. Norbert Casteret next to the Montespan Bear, soon after he discovered it. |

Also in Montespan a horse engraved on the clay wall can be seen.(Fig 6)

|

| Fig. 6. The horse engraving (30 cm long) showing large round marks on and around it. Montespan. |

This horse is covered in large round marks similar to those of the bear and lion and were probably made by throwing spears at it or simply making the marks to represent that idea. The resemblance of this horse to one which is painted in Pech Merle (Fig 7) is striking.

|

| Fig. 7. Painting of horse at Pech-Merle with round marks on and around the body. |

The motive behind the circular marks that have been made all over it and another one on the same wall must surely be the same. Another beautiful example is the engraved bison at Niaux (Fig 8).

|

| Fig. 8. Bison engraved on cave floor at Niaux. The round marks have been made by dripping water. |

Links between ancient and modern rituals

This inevitably begs the question, were their rituals the same and based on the same beliefs?

To answer this question we should consider the following facts:

a) up until the last hunter-gatherers known, there was a fundamental belief that both man and animals possess a spirit and neither is superior to the other

b) they felt sorrow and remorse after killing what they considered a fellow animal, even though this was necessary for their survival

c) they also experienced fear as they believed that the spirit deprived of its physical body would wander angrily and may try to take revenge thus posing a direct threat relative to its size and ferocity or indirectly by persuading its living counterparts to disappear, so thwarting Man's hunting possibilities

For these reasons then, Man believed it was necessary to pay homage to the dead animal and to appease its angry spirit, through some rituals.

Rituals surrounding the bear cult

Some 20,000 years ago hunters in Montespan, having successfully killed a bear, modelled a body from clay to provide a physical frame for the dead animal's spirit to reside in. Just as the Siberian tribes, these people would have both worshipped and hated the bear at the same time, hence the marks left by the spears. The model was located deep inside the cave in a place where it would not be disturbed by people since it was a dangerous animal that could do great harm. Likewise, no footprints or any other outward sign of those responsible for the model can be found nearby since they would have abandoned the cave as silently as possible, erasing all traces that might allow the spirit to come after them.

In Tuc d'Audoubert, about 5,000 years later the same kind of rites would have been performed centred round the bison modelled in clay. Some mystery surrounds the supposed children's heelprints leading away from the bison and amongst clear,larger footprints. If we accept they were made by children, due to their reduced size, were they allowed to play in such a sacred place? Many of those that maintain they were made by children claim they were performing some rite, some say of initiation, where they would have had to walk on their heels with the toes in the air.

Perhaps the imprints were left by the artists themselves as they backed away quietly from the bison where the spirit was now supposed to be. It would have been of utmost importance to them that they did not disturb the spirit as they were leaving, that as they did so they did not take their eyes off it as a precaution and that they left behind no recognisable tracks that could identify and locate them. Backing away on their heels then, the suction created as they lifted their heels out of the mud would have reduced the size of the marks left behind instantly.

The evidence from these two sites remains to this day but this practice of constructing a model bear would surely have been more commonplace. It is likely they made similar structures from frames made from branches and stuffed with dried grasses or reeds, all perishable materials and therefore long since disappeared.

TRANSITION TO PAINTING

Sculptures in caves are a rare find. What is much more common is paintings on walls of caves. Modern dating techniques indicate that the trend went from sculpture through bas-relief to finalise in the more abstract, and of course less time-consuming, two dimensional paintings. This evolution from the concrete to the abstract is common in the history of mankind and is perfectly reflected in the previous examples: the rough clay figure covered with the bear hide of Montespan, the more sophisticated carving of just one side of the bison in Tuc d'Audoubert and finally the more commonplace paintings which often deliberately utilised the uneven rock surface.

So most paintings and engravings done on walls or blocks of stone will be related to these spirit-dwelling rituals that were previously in the form of sculptures. With the passing of time the three dimensional figures covered in hide (like the Montespan Bear) were simplified to "half models" like the bison of Tuc d'Audoubert or the bas-reliefs of Cap Blanc. Then they began to paint and engrave on the wall of the cave where its cracks and bulges insinuated the shape of the animal they wanted to represent. Later, a flat wall surface or block of rock would have been sufficient for their two-dimensional paintings which sometimes they would shade to suggest the three dimensions. The paintings become more and more simplified and abstract until finally they seem to only do engravings.

Although this seems to be a logical chronology, some evidence contradicts it. It is not that simple, as forms that are the most abstract are not always the most modern and some engravings appear to be older than some of the paintings. In spite of the fact that it seems any support for the spirit was sufficient to perform its function, on special occasions or depending on the availability of skilled artists, a more detailed and better quality image could be achieved, thus giving them more satisfaction in their handiwork. On the whole, though, it is not the way the painting looks which is important so much as the results obtained from having represented the animal as, for example, in many panels we can see where they have painted over drawings already existing or modified them making use of some of the lines. In doing so, earlier images would often be spoiled or erased, but as they did not consider this '`artwork" then this was not taken into consideration. What they were doing was providing a kind of virtual body for the spirit of the dead animal to reside in. In this way they achieved several goals;

1. The spirit of the (sometimes dangerous) hunted animal would not be able to seek revenge on its slayers if it was trapped in the picture

2. For the same reason, this spirit could not tell its living counterparts who the culprits had been, which would have lead them to perhaps disappear from the area

3. By doing the painting in a deep unused part of the cave (Group D animals according to Leroi-Gourhan's classification)they could keep spirits of dangerous animals at a safe distance from them

It is important to note that these rituals were performed after the hunt and not before. So the paintings were not intended to propitiate immediate hunting but rather to ensure future kills would not be prejudiced as a result of the slaying of this animal.

PAINTINGS OTHER THAN ANIMALS

If we admit this theory, then what about the figures which seem to be semi-humanlike the one at the centre of the panel in the sanctuary of Les Trois Freres (Fig.9),

|

Fig. 9. Therianthropic figure at centre of panel, Trois Freres, Ariège.

|

another in a different chamber (Fig 10)

|

Fig. 10. Another therianthropic figure in Trois Freres, Ariège.

|

|

Fig. 11. Therianthropic figure in Gabillou cave.

|